Improve your Spanish conversation skills

It’s essential to improve your SPANISH CONVERSATION SKILLS for the DELE/ SIELE exams and the OPI tests

You have to improve your Spanish conversation skills to do well in exams like the DELE diploma or “el examen DELE ” because it’s all about testing the ability to communicate effectively in Spanish, in real-world situations. This is equally true for the DELE’s new online twin, the SIELE exam, and for it American equivalent, the OPI.

Most candidates who fail the DELE exam (some 30% typically do), fail because of having failed the oral test. In fact, 70% of failures are due to having failed the oral test.

So, how do humans gain the ability to converse? After all, small children achieve that skill, without having had any formal language tuition… What can you learn from neuroscience, to improve your Spanish conversation skills?

How should you as an an adult approach learning, so that you will be able to converse in Spanish? There are many conflicting theories, plus ingrained teaching habits stretching back many generations, regarding how best to achieve proficiency in a foreign language. But of late, neuroscience has given us very important insights into how the brain actually processes the acquisition of language. This neurological data has taken the debate out of the realm of speculation (where it had lounged for most of history) into proper understanding of the processes involved.

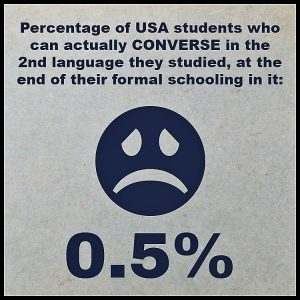

One thing that we have known for some time with certainty, is what DOESN’T work; it has been empirically proven that the traditional school or college-style teaching of a second language fails miserably in producing alumni with the capacity to maintain even a basic conversation at the end of their schooling. Recent figures from the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) show that only 0.5% of school / college alumni who majored in a foreign language, actually achieve that level of competence. Most students taught the traditional way, give up on learning a second language, and those who do finish, have forgotten practically all they had learnt in just three to four years.

In this blog post I will introduce some of the latest and best theories and methodologies for developing proficiency at conversing in a foreign language. This introduction of theory is intended only as a quick orientation for the practical advice which comes at the end of this blog post. I will be sharing with you our own battle-tested tips for developing your conversational ability in Spanish, so that you can ace the DELE / SIELE exam or the OPIc.

The Human Instinct for Language:

To understand how to improve your Spanish conversation skills, you first and foremost have to understand how the human brain functions when it comes to “learning a language” – or, more correctly put – how we acquire a new language: i.e., develop the ability to communicate in it. (Babies don’t set out to “learn a language”; they instinctively acquire the ability to communicate, just as they acquire the ability to walk upright – both much more through PRACTICE than through abstract learning of theory). Understanding this process is certain to help you in cultivating the right mind-set and study methods for making your DELE / SIELE exam and OPI preparation effective.

To understand how to improve your Spanish conversation skills, you first and foremost have to understand how the human brain functions when it comes to “learning a language” – or, more correctly put – how we acquire a new language: i.e., develop the ability to communicate in it. (Babies don’t set out to “learn a language”; they instinctively acquire the ability to communicate, just as they acquire the ability to walk upright – both much more through PRACTICE than through abstract learning of theory). Understanding this process is certain to help you in cultivating the right mind-set and study methods for making your DELE / SIELE exam and OPI preparation effective.

It is recognized that the two most important abilities that set us humans apart from other primates and the rest of the animals in general, is our ability to walk upright and our ability to communicate. Both are vital survival skills. From the survival standpoint the acquisition of mobility is an early imperative. Walking is also a less complex task than the heavily brain-driven skill of oral communication, so babies master that first. It has been shown, though, that listening to the mother’s voice starts already in the womb. Once the toddler is mobile, the brain’s major developmental focus for the next three to five years shifts almost exclusively to honing the ability to communicate verbally.

The ability to master language has been described by the psychologist and cognitive scientist Steven Pinker (in his seminal book “The Language Instinct”) as the “preeminent trait” of the human species, as well as our “most important cultural invention … a biologically unprecedented event irrevocably separating him from other animals.”

For our present purpose, probably the most important observation by Pinker is that language isn’t an academic subject that we are formally taught. Neither do we need, as toddlers, to consciously study it, in order to develop this skill. “Instead, it is a distinct piece of the biological makeup of our brains. Language is a complex, specialized skill, which develops in the child spontaneously, without conscious effort or formal instruction…”

While some cognitive scientists describe language as a psychological faculty or a neural system, Pinker prefers to refer to it as a human instinct, because the term instinct “…conveys the idea that people know how to talk in more or less the sense that spiders know how to spin webs”, which spiders are able to do without having had any formal education in design or engineering, but simply because they have “spider brains, which give them the urge to spin and the competence to succeed.”

“Superior pattern processing (SPP) is the essence of the evolved human brain”

In an article in “Frontiers of Neuroscience” (2014; 8:265) Mark P. Mattson used the above title to describe that aspect of the human brain which allows us to do things that other primates or animals can’t. Mattson says: “The types of pattern processing that appear to occur robustly, if not uniquely in the human brain and are therefore considered as SPP include: (1) Creativity and invention … (2) Spoken and written languages that enable rapid communication of highly specific information about all aspects of the physical universe and human experiences; (3) Reasoning and rapid decision-making; (4) Imagination and mental time travel which enables the formulation and rehearsal of potential future scenarios; and (5) Magical thinking/fantasy… The human brain is remarkably similar to the brains of non-human primates and lower mammals at the molecular and cellular levels, suggesting that the human brain deploys evolutionarily generic signalling mechanisms to store and retrieve large amounts of information and, most remarkably, to integrate information in ways that result in the generation of new emergent properties such as complex languages, imagination, and invention.”

In an article in “Frontiers of Neuroscience” (2014; 8:265) Mark P. Mattson used the above title to describe that aspect of the human brain which allows us to do things that other primates or animals can’t. Mattson says: “The types of pattern processing that appear to occur robustly, if not uniquely in the human brain and are therefore considered as SPP include: (1) Creativity and invention … (2) Spoken and written languages that enable rapid communication of highly specific information about all aspects of the physical universe and human experiences; (3) Reasoning and rapid decision-making; (4) Imagination and mental time travel which enables the formulation and rehearsal of potential future scenarios; and (5) Magical thinking/fantasy… The human brain is remarkably similar to the brains of non-human primates and lower mammals at the molecular and cellular levels, suggesting that the human brain deploys evolutionarily generic signalling mechanisms to store and retrieve large amounts of information and, most remarkably, to integrate information in ways that result in the generation of new emergent properties such as complex languages, imagination, and invention.”

This tendency of the human brain to seek and process patterns has been widely documented in science. In layman’s terms, Ackerman wrote in Time Magazine on 15 June 2004: “Pattern pleases us, rewards a mind seduced and yet exhausted by complexity. We crave pattern, and find it all around us, in petals, sand dunes, pine cones, contrails. Our buildings, our symphonies, our clothing, our societies — all declare patterns”. This was quoted approvingly by Psychiatry professor Bernard Beitman in “Psychiatric Annals” (39:5 / May 2009) under the heading: “Brains seek Patterns in Coincidences” where-in he stated: “Our brains seek coherence, structure, and order. Words and numbers order perceptions. Words and sentences package complex experiences … The brain wants to complete patterns … We can feel its pleasure in making a correct connection.”

“Languages as an advanced pattern encoding and transfer mechanism”

Addressing language specifically (under the above heading) Mattson went on to write: “Language is the quintessential example of the evolved SPP capabilities of the human brain… Language involves the use of patterns (symbols, words, and sounds) to code for objects and events encountered either via direct experience or communication from other individuals. However, despite it being a remarkable leap forward in evolution, language may not involve any fundamentally new cellular or molecular mechanisms; instead, language is mediated by recently evolved neural circuits integrated with older circuits, all of which utilize generic pattern processing mechanisms. Remarkably, the learning of languages and the potentially infinite number of stories (word sequences) that an individual can construct are accomplished using a finite number of neurons that is established during early brain development … Presumably, the synapses involved in language are “strengthened” by repetition (listening and talking, and reading and writing).”

It is only necessary to recall one’s own childhood to know that we developed the ability to communicate verbally without any formal teaching. As toddlers we didn’t study grammar, but from about age three and a half, we could construct phrases grammatically correctly. Where we did make “mistakes”, it usually was when the supposedly “correct” English form deviated from the general pattern we had correctly discerned – as in a child saying two “oxes” instead of saying two oxen, because the regular pattern for forming the plural in modern English is by adding an “s” (like in two boxes, or two cows). Oxen is a relic from the past, which has somehow clung on – unlike the word “kine”, which until a few centuries ago was the correct English plural of cow, but which was jettisoned in favor of cows (with “cows” probably before then regarded as child-speak).

As little kids, we didn’t think of particular verbs as being distinct conjugations of some infinitive form – we simply knew that that was the right word for that particular phrase and context. Our ear told us if another child used a word incorrectly, without us being in any way able to explain why it was wrong. We developed our language skills by getting to know words as simply words, plus the familiar patterns of stitching them together in phrases.

First grammar handbook for an European language – Castilian (Spanish), 1492

The advent of grammar studies:

It is obvious that the patterns of languages weren’t ever formally designed and ordained by committees of elder cavemen laying down grammar “rules”. Languages grew spontaneously, constantly undergoing local variations and unstoppable evolution at the hand (or rather, tongue) of the common folk.

The first visible signs of language standardization started emerging with the advent of writing. The first formal grammar book for an European language was only published in 1492, for Castilian, which now is the national language of Spain. In it, its author, Antonio de Nebrija, laid down as first fundamental rule that: “we must write as we speak and we must speak as we write”. What he insisted upon, therefore, is that researchers and academics should not invent language rules, but must observe and record that which actually exists, with all its irregularities (the concept of grammar “rules” is actually unfortunate, because of the connotation that the word “rules” have of being something authoritatively ordained – with hindsight, it would have been better to speak of grammar patterns).

Because of the natural eagerness of the human mind to create order by means of identifying patterns, it was inevitable that languages would eventually be formally studied. The study of grammar would come to consist of tabulating the patterns evident in any language, such as those for word modification (morphology – for example, the conjugation of words) or the protocols of phrase construction (syntax). It is evident that, by learning and knowing these “rules” or rather patterns, one would be able to predict likely constructs. Now, if we take any sport, knowing the rules of the game isn’t – in and of itself – going to make you a great player. The latter depends i.a. on one’s ability to APPLY such theoretical knowledge instantly and intuitively in actual game settings. This analogy very much resembles the DELE / SIELE exams and the OPI, in which there are no questions on the rules of grammar as such. Instead, all the focus is on the candidate’s ability to apply that theoretical knowledge in real-world communication. (Such tests based on communicative competencies, in any event will quickly enough show the examiner whether you know the “rules”.).

Unfortunately, the traditional school system requires standardized curricula and methodologies. This is so because, in order for school tuition to be feasible in practice, teaching classrooms full of students all at once, there just isn’t scope for individualization. And there are many other subjects to be taught, in addition to a foreign language. Therefore, for the foreign language student there cannot be the constant immersion in his target tongue that the typical native-speaking toddler is exposed to every woken hour (in school and college, time for studying foreign languages is limited – usually only some four to five hours per week, homework time included, is dedicated to learning a second language). Furthermore, it is logical that schools – which are subject to severe constraints of time and organization, whilst dealing with entire class-groups and not individuals – are by the nature of these limitations focused on imparting theoretical knowledge of rules, and not on the individual coaching required to develop actual communicative ability.

As a consequence, schools and colleges are mostly teaching the theoretical foundations of a foreign language, with a focus on reading and writing (all pupils can practice to write at the same time, but certainly all can’t practice to speak at the same time). Quite naturally, therefore, schools are setting written exams to test groups of students’ knowledge of that which the schools have been teaching, namely theory such as the rules of grammar. Schools are not structured, nor disposed, to focus primarily on the individualized testing of each student’s ability to engage in an actual conversation, one by one. Which explains why only 0.5% of US students end up being able to converse in the foreign language they have studied. It’s like teaching and testing football spectators for their knowledge of the rules, instead of coaching and assessing the skills of actual, competent football players.

As a consequence, schools and colleges are mostly teaching the theoretical foundations of a foreign language, with a focus on reading and writing (all pupils can practice to write at the same time, but certainly all can’t practice to speak at the same time). Quite naturally, therefore, schools are setting written exams to test groups of students’ knowledge of that which the schools have been teaching, namely theory such as the rules of grammar. Schools are not structured, nor disposed, to focus primarily on the individualized testing of each student’s ability to engage in an actual conversation, one by one. Which explains why only 0.5% of US students end up being able to converse in the foreign language they have studied. It’s like teaching and testing football spectators for their knowledge of the rules, instead of coaching and assessing the skills of actual, competent football players.

The foregoing is not a condemnation of schools – in many ways the traditional grammar-based approach to foreign language teaching was and is what is practically possible, and no informed teacher is under any illusion that it would, in itself, be enough. Because humans instinctively seek for patterns, it is clearly useful that the patterns inherent to any language’s grammar be identified and codified, and also that these be learnt. It obviously is a faster way of becoming aware of such patterns than simply by absorbing them subconsciously, in the course of years of unstructured immersion. But it is not enough to simply know these rules, if one is to acquire the capacity to communicate effectively. Because while we may be well aware of some rule, if our minds and tongues aren’t practiced in applying it in conversation, then something contrary is likely to slip out – no matter how well we may have “known” that that was the wrong way of phrasing it.

Another major drawback inherent to the traditional way of teaching, is that it inevitably leaves the student with the impression that language consists of individual words, which must be strung together in accordance with set rules, such as that of conjugation – like stringing individual pearls on a necklace. In reality, though, language for the most part consists of “chunks” of words in the form of well-established phrases with agreed meaning.

As kids we pick up and become skilled in using these “chunks”, like: I am going to school; I am going in the car; I am not going to grandma’s etc. We comprehend that the basic chunk stays the same, we only have to change some words to suit the need of the moment. This truth was recognized some two decades ago by Michael Lewis, who called for a new, complementary approach to the traditional way of teaching language, which he called the “lexical approach”. This approach was not intended to replace traditional learning, but to supplement it; Lewis and his followers see it more as an enhanced mind-set, a better understanding of how we actually acquire language, which would broaden the learning methodologies beyond their traditional focus and strive for an outcome of actual conversational competency.

The Lexical Approach:

Olga Moudria wrote an excellent summation of the Lexical Approach, published by the ERIC Clearing House on Languages of Washington DC. Here are some extracts: “The lexical approach concentrates on developing learners’ proficiency with lexis, or words and word combinations. It is based on the idea that an important part of language acquisition is the ability to comprehend and produce lexical phrases as unanalysed wholes, or “chunks,” and that these chunks become the raw data by which learners perceive patterns of language traditionally thought of as grammar (Lewis, 1993, p. 95). Instruction focuses on relatively fixed expressions that occur frequently in spoken language, such as, “I’m sorry,” “I didn’t mean to make you jump,” or “That will never happen to me,” rather than on originally created sentences (Lewis, 1997a, p. 212).” (A key concept that Moudria points to here, is that we comprehend and internalize word chunks without first analysing them – i.e., grammar doesn’t enter into the picture).

She continues: “The lexical approach makes a distinction between vocabulary–traditionally understood as a stock of individual words with fixed meanings–and lexis, which includes not only the single words but also the word combinations that we store in our mental lexicons. Lexical approach advocates argue that language consists of meaningful chunks that, when combined, produce continuous coherent text, and only a minority of spoken sentences are entirely novel creations. The role of formulaic, many-word lexical units have been stressed in both first and second language acquisition research…

“Comprehension of such units is dependent on knowing the patterns to predict in different situations. Instruction, therefore, should center on these patterns and the ways they can be pieced together, along with the ways they vary and the situations in which they occur…

Moudria concludes:” Zimmerman (1997, p. 17) suggests that the work of Sinclair, Nattinger, DeCarrico, and Lewis represents a significant theoretical and pedagogical shift from the past … they challenge a traditional view of word boundaries, emphasizing the language learner’s need to perceive and use patterns of lexis and collocation. Most significant is the underlying claim that language production is not a syntactic rule-governed process but is instead the retrieval of larger phrasal units from memory. Nevertheless, implementing a lexical approach in the classroom does not lead to radical methodological changes. Rather, it involves a change in the teacher’s mindset.

Moudria concludes:” Zimmerman (1997, p. 17) suggests that the work of Sinclair, Nattinger, DeCarrico, and Lewis represents a significant theoretical and pedagogical shift from the past … they challenge a traditional view of word boundaries, emphasizing the language learner’s need to perceive and use patterns of lexis and collocation. Most significant is the underlying claim that language production is not a syntactic rule-governed process but is instead the retrieval of larger phrasal units from memory. Nevertheless, implementing a lexical approach in the classroom does not lead to radical methodological changes. Rather, it involves a change in the teacher’s mindset.

Donovan Nagel of the Mezzofanti Guild summed up the lexical approach very effectively in layman’s terms: “Languages are acquired in prefabricated chunks – words, collocations and expressions that we hear repeatedly. This is why kids go from babble to speaking – to the amazement of their parents – seemingly overnight. To give you an example, ‘I want’ is a chunk. You’ve used those two words together in that order a multitude of times in your lifetime. It’s a set expression that you heard and learned as a whole, and are able to create an infinite number of expressions by adding another chunk (a name or an action). Thus, ice-cream and to go are other chunks that you’ve also learned. What we do as fluent speakers is essentially put together or insert pieces of prefabricated language. Very little of what we actually say is original content.

“I would go a step further and say that every verb tense you know was learned as a prefabricated item. For example, you didn’t learn the verb write and then learn how to conjugate it. You learned I write, she writes, they write, etc. as whole items and over time you gained an ear for what sounds right and what doesn’t. When you hear something that doesn’t quite sound correct (e.g. they writes, he writed) you immediately detect the error – not because you’re aware of grammar, but because you’re so used to the correct, prefabricated forms that anything else doesn’t sound right.”

Barriers to adults developing conversational competency in a foreign language: The main barriers to communicating effectively, fluently and confidently in Spanish as foreign language can be summed up as follows:

- Lack of a sufficient memorized and rehearsed lexis (consisting of an ample vocabulary of words correctly pronounced, plus expressions, idioms and common phrase “chunks”, including link phrases);

- Insufficient knowledge of the grammatical patterns of the language (its word morphology and the syntax for phrase construction), and lack of practice in the instinctive and fluent, correct use of these patterns;

- Inability to correctly form Hispanic sounds (phonology) because of lack of sufficient guided practice, not adapting the body’s articulation tools to the Hispanic way of forming sounds, plus inhibition; and

- An un-attuned ear, not able to correctly capture and understand what others are saying, particularly in the case of accents and dialects.

To meet these four direct challenges just mentioned, some related innate ones also have to be overcome. Foremost is the need to undo unilingual mother-tongue rigidity (which is present in those who don’t yet fluently speak any foreign language). By this is meant that we have been exclusively conditioned from early childhood, to speak in the manner and style of our own cultural peer group, with our mouths knowing only how to form the sounds of our mother tongue. Apart from this physical rigidity, there’s often also a mental one associated with unilingualism, namely that such persons don’t want to see that there are many different ways in which languages can in fact construct phrases – ways that, though different, in themselves do have an internal logic of their own, which is no less logical than that of the familiar structure of their mother tongue. (This tendency to throw the hands up in the air in frustration and say that “the Spanish way makes no sense” is common among those who are subjected to tutoring based essentially on learning grammar without sufficient emphasis on lexis, and without having been given any explanatory reference framework for the historical why’s and how’s of the differences between the two languages).

Such rigidity restricts conversational mental agility, because we think in our mother tongue and thus first have to mentally translate before we speak. It also inhibits the ability to accept and mentally “own” the lexis, grammatical patterns and structure of Spanish – which sometimes are very different from those of English – as being equally valid and logical in its own right.

Unilingual rigidity also restricts articulation (mouth movement etc.) and body language to one rigid mould. This stems from lifelong conditioning of the body’s articulation tools through having been used in only one cultural/linguistic mode, forming sounds for the letters of the alphabet in one way only. To illustrate – a lifetime of pressure to conform to, for instance, a “stiff upper lip” style of verbal expression will clearly limit one’s ability for sometimes exuberant Latino-style expression, if it is not recognised and consciously addressed. Such rigidity in the tools of articulation negatively impacts ability to pronounce intelligibly (like Orientals having difficulty with “RRR” and Anglos with the letter “J”, saying “HHHoasey” instead of “GGGosy”).

Another important debilitating factor is our inhibitions, related to our adult ego-awareness, because we fear making mistakes in front of others. This causes us not to want to practice conversing with others, and we become part of a wallflower syndrome.

OUR TOP TIPS FOR HOW TO IMPROVE YOUR SPANISH CONVERSATION SKILLS

The WHAT of becoming proficient in conversation:

The first thing to get right, is mind-set. Your objective should NOT be “I want to learn Spanish” (because that is aimed at acquiring theoretical knowledge about the language). You should consciously decide that “I want to develop the capacity to converse in Spanish” (which entails not only knowing the theory, but the practiced and honed skill of integrating and applying your knowledge in real-world situations). What you want to be, is an accomplished football player, not just a coach potato football rules boffin.

With your objective clearly defined, it is important next to identify the skills and knowledge sets that are essential to develop, in order to acquire the ability to converse in Spanish. These elements then become the “to do” list of your preparation plan. The ultimate phase will be to add to this “what to do” list, the very important “how to do” component.

What, then, is necessary, in order to be able to actually maintain a conversation in a foreign language? You must firstly have the ability to understand what your interlocutor is saying to you, and secondly you must be able to make yourself understood.

For both understanding and being understood, you first of all need something that actually, for the DELE diploma, is one of its four main oral exam scoring criteria, namely a sufficiently ample “linguistic scope”. This means that you do have to know (i.e., have learnt to the point of having committed to memory and thus have fully internalised) the words, expressions and common “word chunks” making up the lexis of the language, so that you can identify them upon hearing, as well as instantly reproduce them in your own oral expression. This essential knowledge of words and patterns entails knowing the semantics or meaning of words, the phonology or sound of the word, and its morphology or form, the latter signifying the way a particular word is morphed (through conjugation, for example) to convey different meanings.

The second DELE oral exam scoring criteria is “correctness”, meaning correct word selection in terms of semantics, correct pronunciation in terms of phonology, correct morphology (in terms of how you have, for example, conjugated a verb), and correct syntax, relating to how you have strung together word chunks to make phrases and sentences.

The DELE scoring guidelines do emphasize that they are not going to be overly finicky about the theory, as long as comprehension on the part of your listener is not made difficult or impossible by your level of incorrectness. This is, of course, how real conversation in a foreign language actually functions (or doesn’t); your listener can, as an intelligent native speaker, compensate for your small errors of syntax or such things as gender accord, even foe wrong verb conjugation – what he or she cannot compensate for, is if you completely lack the appropriate words to say what you want, or pronounce them so incomprehensibly that your listener’s eyes simply glaze over.

This is to say that, when it comes to the importance of “correctness” in conversation, knowledge of lexis or vocabulary – that is, of the correct word / phrase – and practiced knowledge of how to correctly pronounce it, are significantly more important than knowledge of the “rules” of grammar. In fact, if you are still obliged when you want to say something in Spanish to first try and remember, and then to calculatedly apply these grammar rules in order to mentally construct a phrase before you can utter it, you will have a serious problem in maintaining any kind of conversation. This is the difference between sitting an end-of-school written exam, where you have time to calculate how to apply rules, and real-world conversation, which is an instantaneous give-and-take. Instead of relying on calculated application of rules (which usually signify that you are still thinking in your mother tongue and first have to translate from it) you need to have fully internalized the patterns of Spanish speech (as you had done as a kid, with your mother tongue). Having internalised these patterns, it rolls out correctly almost without conscious thought as to how to say something (thus leaving you free to focus completely on the really important thing, namely the substance of what you want to convey).

The third DELE oral exam scoring criteria is “coherence”. Are you making sense to your listener? This doesn’t only involve having an ample linguistic scope and being sufficiently correct in terms of your Spanish, but also involves the normal rules of logic in the ordering of your thoughts, just as would apply in your mother tongue. You must be able to structure your discourse logically, for example with clear introduction, a sensible body of substantiation, and a persuasive conclusion. Coherence demands that your mind must be free to give a logical presentational structure to what you want to say, without your mind needing to be overly occupied with the grammar and lexis of how you need to say it. Again, this comes down to having sufficiently internalized the patterns of the language so that you can reproduce it correctly almost without conscious effort, like you do with your mother tongue. This, in turn, comes down to expertly guided practice, practice, and then more practice.

The last of the four DELE oral exam scoring criteria is “fluency”. In real life, conversation breaks down when there is no fluency – when you have to constantly interrupt your interlocutor because you could not understand something that he/she said, or when you yourself cannot find the right words or correct pronunciation or appropriate syntax to comprehensibly say what you need to say. Once again, if you need to first translate for yourself and do a rules-based calculation of how to say something, then there will be no fluency. You need to have the lexical patterns of Spanish sufficiently internalized. Especially important to the fluent flow of conversation (and also in the DELE scoring) is the appropriate use of link phrases in order to fluently join up different thoughts or sentences – and not end up uttering a disjointed series of unconnected phrases. You know from conversation in your own language, how important link phrases are – words such as “accordingly”, or “on the other hand” or “as you know” or any of the many such devices that we use to fill blank “think time” between sentences, and to link them together. These are some of the most fixed and most used “word chunks” in the lexis of any language, and knowing these patterns are essential to fluency.

To recap – the what of Spanish that we need to internalize in order to be able to maintain conversation, are the patterns of the language. These are its lexical patterns, of words and word chunks (including their meaning, pronunciation and the patterns for morphing words to signify different meanings in terms of time, number and the like). There are also the patterns of syntax (how words and phrases are strung together to form coherent sentences). This knowledge of patterns we have to internalize, and practice over and over so that we can reproduce it instantaneously without much conscious thought. Without such internalization of the lexical, phonological, morphological, and syntactical patterns of Spanish, you cannot hope to achieve the sufficiently ample linguistic scope, correctness, coherence and fluency that will be required in order to maintain a meaningful and effortless conversation that can focus on substance, rather than constantly succumbing to getting stuck on form.

The HOW of developing the ability to converse in Spanish:

Developing the knowledge and skill sets required to maintain a conversation in Spanish, take place essentially in the same way as you learnt your mother tongue as a child (meaning from toddler to teen), but with certain facilitating and enhancing tools added which toddlers obviously can’t yet access.

Learning the patterns: The basic manner in which your Spanish will develop, will be by means of assimilating patterns. You can check with just about any fluent speaker of Spanish as foreign language – they will tell you that they don’t consciously construct sentences based on grammar rules; they speak Spanish the same way as they speak their native English. They do so intuitively and without conscious mental effort, focused on the substance of their message and not on form. They probably will have to do a double take if you start cross-examining them about the intricacies of the morphology or syntax they had just used – the same as you would, if they do the same to you about your native English (you’ll probably respond that you can’t recall why it needs be said that way, but that you know that that’s definitely the way it is).

Learning the patterns: The basic manner in which your Spanish will develop, will be by means of assimilating patterns. You can check with just about any fluent speaker of Spanish as foreign language – they will tell you that they don’t consciously construct sentences based on grammar rules; they speak Spanish the same way as they speak their native English. They do so intuitively and without conscious mental effort, focused on the substance of their message and not on form. They probably will have to do a double take if you start cross-examining them about the intricacies of the morphology or syntax they had just used – the same as you would, if they do the same to you about your native English (you’ll probably respond that you can’t recall why it needs be said that way, but that you know that that’s definitely the way it is).

The importance of immersion: To discern patterns, and especially to internalize them in this natural manner, we have to be scanning a vast amount of Spanish. This can only be achieved through immersing yourself in an environment where you regularly hear, see and have to speak Spanish, just as a toddler masters the patterns of his mother tongue over the space of five to six years of such immersion (reaching school-going age, this knowledge and skill for self-expression just get polished, with the patterns he/she already have internalized being clarified and explained, whilst the child continues to benefit from ongoing immersion).

The importance of immersion: To discern patterns, and especially to internalize them in this natural manner, we have to be scanning a vast amount of Spanish. This can only be achieved through immersing yourself in an environment where you regularly hear, see and have to speak Spanish, just as a toddler masters the patterns of his mother tongue over the space of five to six years of such immersion (reaching school-going age, this knowledge and skill for self-expression just get polished, with the patterns he/she already have internalized being clarified and explained, whilst the child continues to benefit from ongoing immersion).

It is therefore evident that any attempt to learn a foreign language with an approach based just on classroom + homework time (i.e., without the addition of immersion and its parallel of adopting a lexical approach), is not going to result in any better performance than the figure of 0.5% reaching conversation ability, as cited earlier.

The relative importance and correct view of grammar: Again, this is not to suggest that formal grammar should or could be substituted. Grammar as we know it is none other than a handy codification of the enduring patterns of a language, as these have been observed over time by qualified linguists. Using the fruits of their labors will clearly help you identify and understand the patterns a lot quicker than you would be able to do with just your own random observation. The key, however, is mental attitude – you have to study grammar as a very valuable tool, which will help you spot and comprehend the patterns far quicker and easier. Do not study grammar as if it represents the language as such, as if knowing the “rules” of grammar could or should be – in and of itself – the ultimate objective. Please realize that knowledge of grammar is no more than a convenient crutch in the early phase while you are still hobbling along, whilst not yet having fully internalized the patterns. Just as you did with your English grammar crutch, you will be discarding it, actually forgetting all about it, as soon as you – figuratively speaking – can walk upright with ease and comfort without it.

How many adult native English speakers do you think ever give a moment’s thought to English grammar in their day-to-day conversations? When last did you, yourself?

Always remember, too, that the language patterns codified under the title of grammar (essentially being word morphology and sentence syntax), are intellectual constructs developed almost organically over ages by communities of humans. Since grammar “rules” are intellectual constructs, any intelligent man, woman or child can therefore mentally compensate for most errors they hear in your grammar, without losing track of the meaning you are trying to convey. Studying grammar isn’t the be-all and end-all of “learning the language”. It isn’t even the most important part of such learning (as evidenced by the ability of others to mentally compensate for your grammar errors, and how quickly this crutch is discarded from your active consciousness, once you’ve reached fluency). Nevertheless, don’t be mistaken – until you are fluent through having fully internalized these patterns of morphology and syntax, you HAVE TO STUDY YOUR GRAMMAR – but do so selectively, as we will show, and with the right mental attitude, i.e. that it is a valuable cheat sheet of essential patterns.

The most vital aspect that you have to focus on in your active learning isn’t grammar. It is studying the patterns of lexis.

Lexis is your top priority: By studying lexis is meant acquiring a suitably ample linguistic scope in Spanish for your particular needs (for example, a missionary doctor is clearly going to require a different lexis to a policeman walking the beat in an immigrant neighbourhood). Lexis consists of vocabulary and phonology (i.e., knowing words and their meaning, as well as how to pronounce them) as well as the learning of “word chunks” and common expressions and idioms. The reason why lexis is deemed more important to conversational ability than grammar, is twofold:

Lexis is your top priority: By studying lexis is meant acquiring a suitably ample linguistic scope in Spanish for your particular needs (for example, a missionary doctor is clearly going to require a different lexis to a policeman walking the beat in an immigrant neighbourhood). Lexis consists of vocabulary and phonology (i.e., knowing words and their meaning, as well as how to pronounce them) as well as the learning of “word chunks” and common expressions and idioms. The reason why lexis is deemed more important to conversational ability than grammar, is twofold:

- As was earlier said, to be able to maintain a conversation, you firstly need to comprehend. If you don’t know the meaning of a word or phrase your interlocutor has used, there is no way you can mentally compensate in order to arrive at a correct understanding of what you’re hearing (apart from asking your interlocutor to repeat and explain). It is therefore axiomatic in preparing for the listening and reading comprehension parts of the DELE exam, that “you have to have knowledge of words and the world” (see our earlier blogpost on this subject). This is just another way of underlining the lexical approach, which goes beyond the semantics of any given individual word to include its situational context, as part of a regular pattern of use. If you don’t have adequate lexical knowledge (i.e., knowing the situational meaning of words and phrases that you hear, and knowing enough about phonology to be able to correctly identify which words you are actually hearing), you cannot hope to comprehend much in the course of any given conversation.

- When expressing yourself orally, lexis is also of vital importance. You have to know the right word or phrase (to the point of not having to search for it), and you have to be able to pronounce it intelligibly. If you don’t readily have the right words and phrases at your disposal, or you cannot pronounce them sufficiently correctly for your interlocutor to be able to identify them, then – even with the best of grammar – there is simply no way that your conversation can blossom because your interlocutor cannot mentally compensate for words that you don’t have and which he cannot divine. He will be as lost as you are.

At this point it is important to underline that one should have realistic expectations about the time and effort it will require to reach conversational ability in a foreign language such as Spanish. The ACTFL has calculated that, for a student of average aptitude, it will require 480 hours to reach “advanced low” proficiency (A2/B1 level in the European Common Framework such as the DELE diploma). This translates into doing forty hours per week (8 hours per day) for twelve weeks solid. To achieve “advanced high” level (i.e., not yet “superior”) will require 720 hours for the average student. For the superior proficiency level that diplomats and the like require, it is generally thought that 1,000 hours of intensive preparation is necessary.

What constitutes immersion, in the internet age? The above does not mean that you have to do 1,000 hours that consist solely of classroom + homework time (we’ve already seen where that gets one!). At DELEhelp we see direct tutorial assistance (one-on-one, via Skype) as comprising just one-third of the time you need to dedicate to developing your proficiency in Spanish. The other two-thirds need to be dedicated to active and passive exposure to Spanish, so that you can become familiar with the patterns in actual use. Immersion doesn’t only signify visiting a Spanish-speaking country and living there for some time. You can immerse yourself totally in Spanish-language books, films, talk radio and news. This is more focused and productive than merely living in a Spanish-speaking environment, because you can select appropriate themes and you can have your tools at hand, such as for jotting down and looking up new words, and adding these to your flashcard list. This combines the mental awareness of the lexical mind-set with all the other traditional learning tools.

There is no doubt that the more time you invest in reading Spanish, the more you will internalize the lexis and patterns of the language, as well as getting to know the Hispanic cultural context – especially if you have given sufficient attention to your grammar as a great tool for helping you to quickly spot and understand those patterns. Reading has the huge benefit of seeing the words, but you need to hear them as well for the sake of phonology (you therefore have to maintain a balance between listening and reading). For this reason, the Spanish telenovela (TV soapy) is a great learning tool, especially those that have subtitles for the hard of hearing, so that you can see and hear the word, and also see its situational context playing out on screen.

In any event, whenever you read, read out loud – this provides good practice to your “articulation tools” to adapt themselves to the Spanish sound system, in the privacy of your own home and thus without any risk to your ego. Better still: tape yourself reading out loud, so that you can pick up your pronunciation errors – you will be surprised how different we all sound in reality, as opposed to how we imagine we sound!

Luckily, such “home immersion” in Spanish is nowadays a free option, thanks to the internet. You don’t have to go live in a Hispanic country anymore (if you don’t want to, that is). Check out this DELEhelp blogpost for a host of links to free sites, ranging from streamed talk radio, through the major Hispanic print press to free e-books and telenovelas. One needs to differentiate between active learning (such as working on your flashcard lists and memorizing them, or doing homework exercises in grammar, in reading comprehension or writing) and passive immersion. The latter can form part of your relaxation, like reading a book in Spanish (if you are a beginner, look for dual text books that have Spanish on one page and the English on the opposite). Every possible minute that you can have Spanish talk radio streaming live, or the TV running telenovelas in the background, is useful – even if you can’t really concentrate on their content, you will pick up phonology as well as words, phrases and patterns. Knowing how kids learn, you shouldn’t underestimate the value of this.

One of the great killers of people’s ambition to master a foreign language, is frustration (next to boredom, especially if they just do grammar exercises!). Frustration can really grow very quickly if grammar mastery is (wrongly) seen as the be-all and end-all of gaining proficiency in Spanish. You may know, for instance, that every Spanish verb can literally be conjugated into 111 different forms, given the number of different moods and tenses in Spanish. If you get stuck on the idea that you absolutely have to memorize each and all of these 111 possibilities in order to be able to converse, the task will seem so daunting that very few will not become frustrated.

Develop your own style of speaking that’s natural and comfortable for you: Here’s another tip – each of us, no matter our language, have a particular own style of speaking that we’re comfortable with. We don’t use all the possible tenses in normal conversation (as some writers may do in penning high literature). Similarly, when conversing in Spanish, you don’t need to have all 111 conjugation options rolling fluently off your tongue. This is especially true in the beginning, while you are still internalizing the basic patterns of Spanish.

Develop your own style of speaking that’s natural and comfortable for you: Here’s another tip – each of us, no matter our language, have a particular own style of speaking that we’re comfortable with. We don’t use all the possible tenses in normal conversation (as some writers may do in penning high literature). Similarly, when conversing in Spanish, you don’t need to have all 111 conjugation options rolling fluently off your tongue. This is especially true in the beginning, while you are still internalizing the basic patterns of Spanish.

What you can do, is to concentrate, for the purpose of speaking, on mastering the present, the idiomatic future and the perfect past tense of the Indicative mood. If you can conjugate these three tenses well, any interlocutor will be able to understand which time-frame you are referring to. These three tenses correspond very well to the way you are accustomed to use tenses in English, because both the idiomatic future and the perfect past in Spanish are compound tenses, using auxiliary verbs (just like in English, which also use compounds with auxiliary verbs to indicate past and future – auxiliaries like “shall” and “have”).

This way of speaking is in fact becoming more common in Spanish, so you won’t be regarded as weird – in the Americas, for example, the idiomatic future tense (futuro idiomatico) is already used exclusively, in place of the traditional conjugated future tense (the idiomatic future tense is constructed by conjugating the verb “ir” + a + the infinitive of the action verb: voy a comer – I am going to eat). For the idiomatic future tense, you only need to learn the present indicative conjugation of one verb, namely “ir”.

The Spanish perfect past tense (perfecto de Indicativo) is constructed with the present indicative conjugation of the verb “haber” + the past participle of the action verb: he comido – I have eaten. The use of the perfecto de Indicativo for indicating the past is becoming more and more common in general use such as in journalistic Spanish, in Spain in particular; so again – you will not be frowned upon or thought a dunce. Because it resembles the way English is constructed, it will come easier to you – also since there is only one conjugation to memorize. (We must emphasize, though, that this approach works for when you yourself are speaking, but because you cannot control the tenses that your interlocutor may choose to use, you have to have sufficient knowledge of the other tenses to at least be able to recognize them, otherwise you may not comprehend what you are hearing or reading; in any event, it is much easier getting acquainted with something to the point of being able to recognize it when used by others, as opposed the level to active learning that’s needed for the purpose of own speech, which demands full internalization to enable real-time application).

For proficiency at conversation, you have to practice speaking (and be guided / corrected): The immersion that we referred to above, needs to go beyond you absorbing written and spoken Spanish. To acquire the skill and confidence to maintain a conversation, you have to have guided practice in speaking. This is often a problem for a home-study student living in an environment where there are few speaking opportunities. Again, though, the internet comes to the rescue, in the form of Skype and its equivalents. Such online tuition and interaction is actually better than what most classroom tuition situations can offer. In the typical classroom you are part of a group, dragged down by the lowest common denominator and by methodologies and curricula that of necessity are generalized, without focus on your particular needs. One-on-one tuition at a residential institution is prohibitively expensive (the actual private tuition itself is very costly, and then you have to add travel and accommodation costs, plus the opportunity cost of being away from work or business). On the other hand, such one-on-one, personalized tuition based on an individualized study plan that’s custom-designed just for your needs and aptitudes, presented via Skype, is very affordable (at DELEhelp, for example, we charge only US$10 per hour of actual Skype tuition, which includes our free in-house study materials as well as our prep time and the time we spend revising your homework and model exam answers; there are no hidden costs).

The great benefit of having your own expert, experienced online tutor (apart from the low cost and the convenience of studying in the comfort of your own home) is that you have someone you can speak to, who will know how to correct and guide you. A relationship of confidence soon develops, so that the natural inhibitions of ego fall away and you can really freely practice to speak. We have already mentioned the vital importance of pronunciation – it is clearly very difficult to perfect this if you don’t have a live human being listening to you and guiding you (no matter what the computer-based interactive packages may claim about their pronunciation software). It is also true that interactive computer packages can tell you if you are answering correctly or incorrectly, in relation to simple things like vocabulary, but can they explain to you? Obviously not.

A useful free supplement for speech practice is the online student exchange, such as iTALKi. This works on the basis that you are connected with a native speaker of your target language, who in turn wants to learn your native language. Of every hour spent with him/her on Skype, you are supposed to speak your target language for 30 minutes while your exchange partner corrects and guides you, and then you switch roles, with you correcting his/her efforts at conversing in English. This is a supplementary resource, because it will at least give you opportunity to practice speaking. The extent to which your exchange partner will really be able to explain things to you, is a matter of pure chance. Take yourself as example – you may well be able to point out to your exchange partner when they make a mistake, and give an example of the right way to say something, but how good is your current recollection of English morphology, syntax and semantics, for really explaining to him/her when they are confounded by something? Nevertheless, the exchange forums are a valuable supplementary resource, and they’re free.

Getting over the ego / fear of failure barrier: A last tip with regard to speaking practice, concerns the barrier in the adult psyche constituted by our natural fear of making a fool of ourselves in front of others. This is perfectly normal, and its inhibiting power is great. There are three distinct ways of overcoming this barrier. The first is to build a relationship of comfort with a trusted tutor, as I mentioned earlier. Another is to get objective proof of your proficiency in the form of certification, such as the gold standard DELE diploma of the Spanish education ministry. This knowledge that you’ve proven that: “yes, I can!” will boost your self-confidence no end.

A third option (which can be integrated with the first) is to create a situation where you, John Smith, aren’t making the mistakes – somebody else is, so it’s no skin off your nose. This approach, which is called suggestopedia, was originally developed in the 1970’s by a Bulgarian psychotherapist by the name of Georgi Lozanov. What it entails, is that John Smith will, for example, arrive at the diplomatic academy, where he will immediately be given a new identity related to his target language – he will become Pedro Gonzalez, a journalist from Mexico City with a passion for football and politics, and an entire back story that John Smith has created for his Pedro identity. All his fellow students and tutors will know John Smith as Pedro, and interact with him as such. This has the benefit of taking John’s ego out of play, plus the benefit of freeing him up to adopt a Latino persona, so that he can escape from his unilingual Anglo cultural and phonological straightjacket and learn to articulate (and gesticulate) like a true Latino. Suggestopedia isn’t the answer to all the methodological challenges of learning a foreign language – it is simply another tool, to be used in conjunction with others. I have seen its effectiveness during my days as head of South Africa’s diplomatic academy (during the transition years to full democracy, before I became ambassador for the New South Africa of President Mandela). I’ve also seen it at DELEhelp – one remarkable fellow really got into the swing of things, designing for himself an identity as a Mexican footballer (soccer player) and every time sitting himself down in front of the Skype camera with his enormous sombrero on his head, dressed in his club soccer shirt and with a glass of tequila in his hand. It wasn’t difficult for him to really get into his new character, which completely freed him of his unilingual Anglo mould and assisted him enormously in mastering the articulation of Spanish phonology in no time. If you think it can work for you, give it a try!

This has been quite a long blog post, but I believe the importance of the subject merits such substantive treatment. Obviously much more can be said. So, if you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to drop me a line – I will do my best to answer, and like everything associated with this blog, my answer will be free and without implying any obligation on your part. You can use the convenient contact form on this page to send me your questions.

Please ask for our FREE DELEhelp Workbook #9 (DELE / SIELE Exam Orientation and Acing Tips) an e-book of some 96 pages; it is a free sample of our in-house study materials, developed especially for English-speakers. Ask for this unique DELE exam preparation book using our convenient contact information form (click on image), and I will send the download link to you, gratis and with no obligation.

You can also ask for our FREE exploratory one hour Skype session, in English with myself, in which I will explain the exams such as the DELE / SIELE and OPI, plus our 1-on-1, personalized coaching methods and answer all your questions (you can use the same contact info form to set up the exploratory Skype session).

Good luck with practicing to improve your Spanish conversation skills! (It is expertly guided PRACTICE that makes perfect).

Saludos cordiales

Willem

Hola,

Me gusta su blog, es muy informativo! A mí me gustaría recibir su Workbook #9 (DELE Exam Orientation and Acing Tips) mucho. Tengo ganas de sacar un diploma de nivel avanzado de DELE algún día pero necesito mucho más practica de hablar antes de hacer eso. Por eso me interesa también sus clases de SKYPE.

Muchas gracias!