Spanish History is part of the DELE Exam Curriculum

The DELE exam’s curriculum doesn’t consist only of grammar – Spanish history is part of the DELE exam curriculum. It is required that students should have a basic knowledge of the history of the Spanish language, and of Spain and the Hispanic world. Just as with grammar, candidates will not be tested directly on such knowledge in the exam. The DELE exam, after all, is concerned with your ability to apply knowledge, rather than simply possessing theoretical knowledge. The exam tests practical, real-world ability to communicate, in writing and speech. But communication is not only about expressing yourself. It is also about comprehending. Just as you need to know vocabulary in order to understand, you also need to know cultural context, if you really want to catch all the nuances. That is where knowledge of Hispanic history, social norms, and traditions, as well as of their culture in general comes in – and that is why these topics are included in the curriculum of the examen DELE.

In this blogpost I will give you a brief overview of how Spain came to adopt a dialect from its far north, called castellano (Castilian), as its national language. There are other regional languages spoken in other parts of Spain, such as Galician, Basque, and Catalan. The Spanish constitution stipulates that these languages have concurrent official status, together with Castilian, in their respective autonomous regions. Native speakers of these regional tongues prefer the term castellano for what non-Spaniards commonly call Spanish, since they consider their own languages to be equally “Spanish”. The Spanish Constitution of 1978 uses the term castellano to define the official language of the whole Spanish State, and calls the regional languages las demás lenguas españolas (lit. the rest of the Spanish languages).

The Spanish Royal Academy, by contrast, uses the term español. Its official dictionary states that, although the Academy prefers to use español when referring to the national language in its publications, the terms español and castellano are regarded as synonymous and equally valid.

The Spanish Royal Academy Dictionary attributes the origin of the name español to the word espaignol, and that in turn comes from the Medieval Latin word Hispaniolus, meaning ‘from—or pertaining to—Hispania’. Other authorities attribute it to a supposed medieval Latin *hispaniōne, with the same meaning. It is said (but not proven) that “hispania” derives from the Phoenician word that means “land of rabbits” (which is the reason behind the banner image of this post).

In the following sections you will see why it is that Spanish history is part of the DELE exam curriculum, even if you are not going to be directly tested on it: having knowledge of the cultural background, will help you with comprehending the situational meaning of words and expressions in their societal context.

Indo-European Pre-History and the Dynamics of Language Evolution

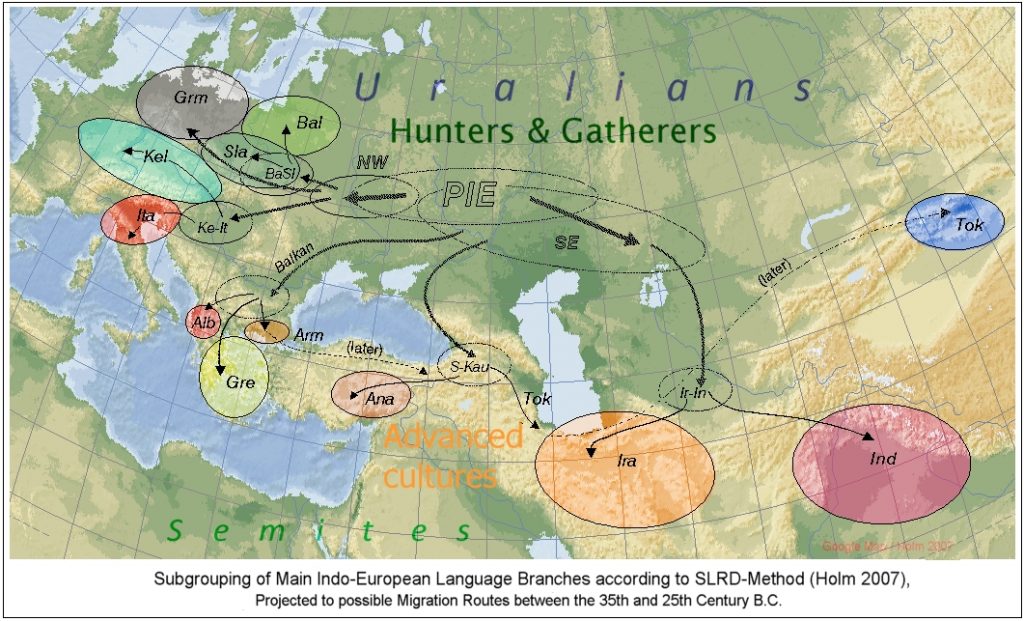

At its root, modern Spanish derives from a common language spoken around 5,000 – 3700 before the Common Era over much of what is today Europe and the Indus Valley in India. This Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) is the common ancestor of the most important modern Indo-European languages (although in Europe and on the Iberian Peninsula other languages not related to PIE do exist, such as Basque). It is believed that PIE may have originally been spoken as a single language (before divergence began) by people living between the Vistula River in Poland and the Caucuses mountains to the East. More precisely, it may have been centered in the Anatolian region of present-day Turkey. The languages derived from PIE show clear inter-relationship in the roots of verbs and in their grammar. These languages include the old Indian language Sanskrit and classical Greek and Latin. The Indo-European language family today consists of seven main branches:

- Germanic (German, English, Dutch, Afrikaans, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish) have some 440 million mother-tongue speakers;

- Indic ( Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Romany – 378M);

- Slavic (Russian, Czech, Slovak, Slovene, Serbo-Croat, Polish, Bulgarian – 250M);

- Iranian (Farsi, Kurdish – 73M);

- Celtic (Welsh, Irish, Breton – (12M);

- Hellenic (Greek – 10M); and

- Romance (Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, Galician, French, Romanian and Swiss-Romansch, which together is the most numerous branch at some 670M native speakers).

Almost counter-intuitively, PIE was not a structurally simple, “primitive” language at all, but in fact a hugely complex one – much more so than modern languages such as Spanish, which have undergone significant simplification over the millennia. For example, PIE used three numbers (singular, dual and plural – as opposed to two in Spanish, singular and plural). PIE also used more moods (“mood” relates to the “state of mind” of the speaker; the mood determines which set of verb terminations to employ when conjugating verbs, such as the imperative mood for giving commands). In modern Spanish everything related to actions that are uncertain, irreal, or that reflect wishes, fears, desires etc., are subsumed into one mood, the subjunctive. PIE, on the other hand, used the subjunctive only for the irrealis, and another mood (with its own conjugations), the optative, for wishes, desires, fears etc. PIE thus had a complex system of morphology. Nouns used a sophisticated system of declension and verbs used a similarly sophisticated system of conjugation.

Almost counter-intuitively, PIE was not a structurally simple, “primitive” language at all, but in fact a hugely complex one – much more so than modern languages such as Spanish, which have undergone significant simplification over the millennia. For example, PIE used three numbers (singular, dual and plural – as opposed to two in Spanish, singular and plural). PIE also used more moods (“mood” relates to the “state of mind” of the speaker; the mood determines which set of verb terminations to employ when conjugating verbs, such as the imperative mood for giving commands). In modern Spanish everything related to actions that are uncertain, irreal, or that reflect wishes, fears, desires etc., are subsumed into one mood, the subjunctive. PIE, on the other hand, used the subjunctive only for the irrealis, and another mood (with its own conjugations), the optative, for wishes, desires, fears etc. PIE thus had a complex system of morphology. Nouns used a sophisticated system of declension and verbs used a similarly sophisticated system of conjugation.

Guy Deutscher, in “The Unfolding of Language: an evolutionary tour of mankind’s greatest invention” describes how all languages are in “perpetual motion”. We, the people, continuously adapt them. The more people there are speaking a language, especially in a diverse, fast-moving, geographically-spread social environment, the more change there will be. This is because we “cook up” languages, and the more cooks we have, the more variations to the recipe (if your family has no outside contact, you will make and eat tamales like your grandma made them, and so will your great-grandchildren). Therefore, the more primitive, slow to evolve, small in number and limited in space a society of language users is, the more complex and regular (i.e., unchanged over time) the language structure is likely to be – as is well demonstrated by PIE.

All languages continuously suffer the ravages of forces seemingly of destruction, but which at the same time serve also as forces of creation. The more we live in accelerated time, using a language that is open to impacts from a wide circle, the more marked the evolution of the language will be. An example is the lot that befell the Classical Latin of the Roman elites, from the start of empire in 29BCE, when “Vulgar” Latin – which had always existed side-by-side with Classical Latin – increasingly replaced it to become the official form (“vulgar” here means “common” or of “the people”, this being the language spoken by the general populace and in the colonies). Classical Latin eventually retained only its written status, mostly in the Roman-Catholic Church. That function, as language of written record, was eventually superseded by the modern regional evolutions of Vulgar Latin, what we call today the Romance languages. Examples of these regional evolutions of Vulgar Latin are French and Spanish, which started appearing in print in the 9th century.

Such evolution is universal, as can be seen also in English (another eventual imperial language with a wide foot-print). A good example is the different versions of the English Bible over time:

1000CE – me ofthingth sothlice thæt ic hi worthe

1400CE – forsothe it othenkith me to haue maad hem

1600CE – for it repenteth me that I haue made them

2000CE – because I regret having made them

A thousand years ago English still had a complex case and gender system, while now it has practically none:

Singular Plural

thæt wæter (the water) tha wæter-u (the waters)

tham wæter-e (to the water) tham wæter-um (to the waters)

thæs wæter-es (of the water) thara wæter-a (of the waters)

An example of remnant impact of gender is the plural of “ox” namely “oxen” – not “oxes” on the pattern of “boxes” – because ox was of the feminine gender and feminine nouns originally ended in the plural on “-en” and not on “-es”.

In fact, English has some 200 irregular verbs, and many more if we add the prefixed forms. The 12 most frequently used verbs in English are all irregular. Irregular verbs – whether in English or Spanish – are not indicative of a language that has stagnated, but of quite the opposite: they speak of dynamic evolution of the broader language.

Inevitably, in most living languages grammatical structure does change, vocabulary adapts, pronunciation comes to sound very different over time, but more often than not spelling seems to lag behind (because, unlike the free-wheeling spoken language, spelling has for some time now been governed by conventions dictated by committees and enforced in schools). As Deutscher observes: “…one could easily fall under the impression that for some reason changes in (English) pronunciation came to an abrupt halt after 1611. But this is just an illusion… And it is precisely for this reason that English spelling is so infamously irrational… it is unfair to say that English spelling is not an accurate rendering of speech. It is – it’s only that it renders the speech of the sixteenth century.”

With Spanish also being an imperial language spoken in far-flung parts, the process of simplification and transformation is already in evidence in Latin America, where the “vosotros” form has been discarded and where the future tense is now exclusively constructed idiomatically with “ir” + the infinitive, instead of using the regular Spanish conjugated future tense.

Humans make language, and linguists now know that humans are inherently lazy and quirky – always prone to taking short-cuts, seeking pronunciations that are easier on the tongue, cultivating dramatic effect by using established words in counter-intuitive manner (like “cool”) yet also prone to following fashion and thereby giving impetus and acceptance to such fads. By these means humans are constantly destroying the old and creating afresh. Far from being abhorrent, this is essential to the vitality and continued serviceability of languages. Humans are also prone to ordaining and structuring, to migrating and colonizing – the effect of which, on language, is well demonstrated by the linguistic history of the Iberian Peninsula.

It is only half-jokingly said that the difference between a dialect and a language, is that the latter had an army and a navy behind it.

Romance / Latin / Italic roots of Modern Spanish

The modern Romance languages (such as Italian, Castilian, Catalan, French and Romanian) form a subfamily of the Indo-European language family. The Romance languages all derive from Vulgar Latin, which co-existed with classical Latin in the Roman Empire. Latin was an Italic language (i.e., Italic referring to the now extinct languages stemming from PIE that were spoken in the Italian peninsula, such as the Latin variants, plus Umbrian, Oscan and Faliscan). Vulgar Latin’s latter-day daughter languages, the Romance languages which took root in the old Roman Empire, are the only survivors of the original Italic languages.

Vulgar Latin (in Latin, sermo vulgaris or sermo pleibus; in English literally “common speech”) was the spoken language of the working class, traders and soldiers who colonized the empire for Rome. Classical Latin was the schooled, written language of the ruling Roman elite. The two forms co-existed side-by-side during the Roman heyday. As Ralph Penny points out in “A History of the Spanish Language” this is illustrated by words such as those for horse, which in Classical Latin was “equus” (thus equestrian sports) but in modern Spanish is caballo, in French is cheval, in Italian cavallo, and in Portuguese cavalo – from the generic term for horse in Vulgar Latin, caballus, which in Classical Latin would strictly mean a “nag” or “work-horse”.

Linguistic History of Iberia before the domination of Spanish (Castilian)

The modern Spanish language’s Vulgar Latin seeds were brought to the Iberian Peninsula by the common Roman soldiers and colonists at the beginning of the Second Punic War between Rome and Cathage in 209 BCE. Prior to that time, several pre-Roman languages (also called Paleohispanic languages), which were unrelated to Latin were spoken in the Iberian Peninsula. These languages included Basque (still spoken today, and unrelated to Indo-European), Iberian, and Celtiberian.

The early Iberians left few traces of their language in modern Spanish: Some of these words are: arroyo (small stream), barro (mud), cachorro (puppy), charco (puddle), gordo (fat), García (family name), perro (dog), manteca (lard), sapo (toad), tamo (chaff).

Toward the end of the sixth century before the Common Era (BCE), a nomadic tribe from central Europe known as the Celts moved into the area and mixed with the peninsula’s then inhabitants, the Iberians. The result was a new people called the Celtiberians, and they spoke a form of the Celtic language. Most of the Celtic words remaining today in Spanish have to do with material things, and with hunting or war. For example: carro (cart), cama (bed), braga (panties, from the typical breeches the Celts wore), camino (road), camisa (shirt), cerveza (beer), flecha (arrow), lanza (lance).

Most of the words of Greek origin found in modern-day Spanish do not come from the pre-Roman period of small-scale Greek colonization along the Spanish Mediterranean coast. They were actually introduced into the Vulgar Latin language later by the Romans adopting from Greek, or were adopted from Greek even later by the Spanish themselves during the post-Middle Ages, to fill the need for scientific terminology. Most of these words refer to education, science, art, culture and religion, like matemática (mathematics), telegrafía (telegraphy), botánica (botany), física (physics), gramática (grammar), poema (poem), drama (drama), Obispo (bishop), bautizar (baptize), and angel (angel).

The Phoenicians – a Semitic, seafaring nation originally from the coast of present-day Lebanon and Syria – founded the city of Carthage on the North African coast (in present-day Tunisia) around a thousand years before the Common Era. By 500BCE, Carthage had evolved into a Mediterranean superpower. During the sixth century BCE the Carthaginians responded to a Tartessian (Iberian tribe) attack on the Phoenician city of Gadir. During this campaign the Carthaginians invaded the Iberian Peninsula and subjugated the Tartessians. The Carthaginians then went on to establish port cities in Iberia, such as Carthago Nova. Meanwhile, Rome had started to emerge as a substantial power in Italy, although its military might had been essentially land-based, as opposed to the maritime strength of Carthage. Inevitably the two powers began to clash, in what became known in the Roman world as the Punic wars.

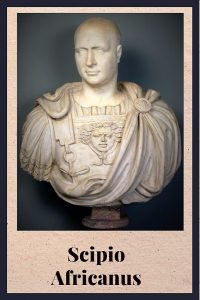

The first war started in 264BCE, when the Carthaginians engaged an ever-expanding Rome in order to retain Carthaginian control over the island of Sicily. Carthage lost, but wasn’t eliminated as rival power. In 218BCE, the Carthaginians provoked the second Punic war, trying to recover territories that they had lost to the Romans during the first war. As part of this second war the famous Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca invaded Italy, via Spain, crossing the Alps with his elephants and Spanish mercenaries. His brother Amilcar Barca remained in Spain (the city of Barcelona derives its name from its Barca founder).

Desperate to force the marauding Hannibal to quit Italy, the brilliant young Roman general Scipio Africanus decided as counter-strategy to cut Hannibal’s supply lines by invading Iberia. He first attacked New Carthage, which he rapidly conquered. Under Scipio’s inspired leadership the Roman Empire systematically took control of the peninsula, and then invaded North Africa itself (landing in modern-day Libya) at last forcing Hannibal to leave Italy in order to defend his homeland. Scipio went on to decisively defeat Hannibal in 202BCE at Zama in North Africa. This assured Roman hegemony in the Mediterranean and consequently in Iberia – where the Romans forthwith imposed their language. Vulgar Latin became the dominant spoken language of the peninsula, and from it, modern Spanish evolved – but not without some considerable twists and turns, as will be shown below.

Desperate to force the marauding Hannibal to quit Italy, the brilliant young Roman general Scipio Africanus decided as counter-strategy to cut Hannibal’s supply lines by invading Iberia. He first attacked New Carthage, which he rapidly conquered. Under Scipio’s inspired leadership the Roman Empire systematically took control of the peninsula, and then invaded North Africa itself (landing in modern-day Libya) at last forcing Hannibal to leave Italy in order to defend his homeland. Scipio went on to decisively defeat Hannibal in 202BCE at Zama in North Africa. This assured Roman hegemony in the Mediterranean and consequently in Iberia – where the Romans forthwith imposed their language. Vulgar Latin became the dominant spoken language of the peninsula, and from it, modern Spanish evolved – but not without some considerable twists and turns, as will be shown below.

It is also very noteworthy that Latinisms in Spanish don’t derive only from the early Roman root stage in its history. After the founding of written Spanish in the 9th century, the modern language very often, throughout the centuries, found itself in need of words to depict the non-material aspects of life. For these it then borrowed abundantly from Latinisms (exactly as did most other modern European languages at the time). It is said that some 20% to 30% of modern Spanish vocabulary stem from such later borrowing.

The Visigoths invaded Hispania during the fourth century of the Common Era. They were a Germanic tribe originally from eastern Europe, but which had earlier entered Rome, where they had lived under Roman rule. Around the year 415CE they entered Gaul and Hispania and expelled the other eastern European barbarian tribes (such as the Vandals) that had settled in the area. Initially the Visigoths were Roman foederati (i.e., a treaty tribe), but they soon broke with the Roman Empire and, after being expelled from Gaul by the Francs, they established their dominion through most of the Iberian Peninsula, with their capital at Toledo. They did not have any great cultural impact, though, firstly because they were small in number (some 200,000 vs. several million Ibero-Romans), and secondly because their Gothic culture was significantly different and seen as barbaric and repulsive. Another contributing factor was that, by the time they entered Hispania, the Visigoths had themselves become in many ways Romanized. It was the Visigoth king Reccared 1st who converted the Hispanic monarchy to Roman Catholicism from around 589 CE, cementing the position of Latin due to the church’s inextricable links to that language.

The Goths themselves thus left no lasting linguistic imprint on Spanish. It is interesting, though, that – during the Latin-American wars of independence against Spain – it was common for te Hispano-Americans to refer derogatorily to peninsular Spaniards as Godos (thus illustrating the negative way the Goths were likely perceived through the ages). Indirectly, the fact that the Visigoths had established their capital at Toledo on the central meseta (which endowed that city with a lasting status) in later years benefited the rise to prominence of the Castilian language, when Castile gained prestige among the ranks of Northern Iberian principalities by reconquering Toledo from the Moors.

At different times during its evolution, Iberian Vulgar Latin and later Spanish, also borrowed words from Germanic languages, such as yelmo (helmet), tregua (truce), robar (to steal/rob), jardín (garden), guiar (to guide), ganso (goose), banco (bench), banda (group – of soldiers etc.).

When we take into account that both English and Spanish borrowed from Greek and Latin, and that both English and Spanish share an Indo-European origin, it is no surprise that the two languages actually have near 40% of their vocabulary in common. Pronunciation of these cognate words does vary, as does spelling, particularly the word terminations used. But these terminations actually follow very clear patterns of conversion between the two languages. When you know these fixed patterns for transforming the cognate words from one language into the other, it actually becomes easy to anticipate how such familiar English cognate words will appear in Spanish, and vice versa – and you will have a sizeable instant vocabulary.

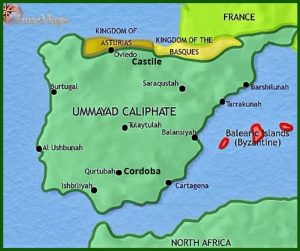

Iberia under the Moors

Arabic-speaking Moors from North Africa conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula from around 718CE. During this Islamic occupation, many of the country’s residents learned Arabic and eventually spoke it exclusively, but Vulgar Latin survived in certain northern kingdoms (such as Asturias) still governed by Christians, as well as among the Mozarabes (the Christians remaining in al-Andalus under Moorish governance, but who were allowed under Islamic law to retain their Catholic religion, due to also being “children of the book”). The Roman-Catholic church exclusively used Latin as language, and was also the font and protector of the written word in the education of the small Christian elites and in church liturgy and correspondence.

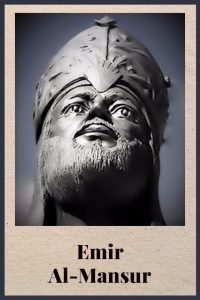

The Muslim conquest was at its height under the caliphate of Córdoba, which had united the Muslim lands in Iberia under central reign and elevated the city of Córdoba to Europe’s foremost seat of enlightenment, tolerance and learning. However, the Umayyad royal lineage was usurped by the regent Al-Mansur after the death of al-Hakam II in 976CE. Lacking own royal credentials, Al-Mansur harkened to populists and fundamentalist Muslims to strengthen his power base, and although he attained fame as a successful military commander, Al-Mansur’s campaigns (especially the burning of the iconic cathedral of Santiago Apostol) incentivized the Christian domains of the North of Iberia to fight back, united and ever more vigorously, under what was to become the enduring Spanish war cry of “for Santiago”.

After Al-Mansur’s death the central reign of Córdoba over Al-Andalus fell apart, with the Muslim lands splintering into taifas or small separate kingdoms. Coupled with the rise of Muslim intolerance and repression of the indigenous Christians, the table was set for the warrior clans from the north to exact their revenge and re-conquer the whole of the Iberian Peninsula, which they systematically did over the following centuries, culminating in the fall of Granada on the 2nd of January in the eventful year of 1492.

After Al-Mansur’s death the central reign of Córdoba over Al-Andalus fell apart, with the Muslim lands splintering into taifas or small separate kingdoms. Coupled with the rise of Muslim intolerance and repression of the indigenous Christians, the table was set for the warrior clans from the north to exact their revenge and re-conquer the whole of the Iberian Peninsula, which they systematically did over the following centuries, culminating in the fall of Granada on the 2nd of January in the eventful year of 1492.

Many Arabic words have, however, entered into Spanish. Today, modern Spanish has approximately 4,000 words with Arabic roots. Most of these words are related to war, agriculture, science and the home, like tambor (drum), alférez (ensign), acicates (spur), acequia (canal, drain), aljibe (cistern, reservoir), alcachofa (artichoke), alfalfa (alfalfa), algodón (cotton), alcoba (bedroom), azotea (flat roof), algoritmo (algorithm), alquimia (alchemy), alcohol (alcohol). The influence of Arabic on Spanish was only on the lexicon (i.e., vocabulary); Spanish did not incorporate any Arabic phonemes into its phonological system. An interesting aspect of the Arabisms in Spanish (which are mostly nouns), is their tendency to start with “al”. This is due to confusion caused among the Vulgar Latins by the very different nature of the Semitic and Latin languages when it comes to the definite article (i.e, “the”). In Arabic the definite article al is invariable in respect of gender and number (thus, always al) whereas in Spanish it is very much variable (el, la, los, las – depending on gender and number). This caused the Iberians to adopt the Arabic noun together with its (fixed) definite article: in Arabic alfalfal therefore means “the falfal” (the lucerne field), whereas the Spanish “el alfalfal” would literally mean “the the falfal (lucerne) field”.

The rise of Castile and the Castilian language

The leading force among the Christian principalities of extreme northern Spain in what today is called the Reconquista was Asturias, the north-western redoubt beyond the Cantabrian mountains, whose leaders became known as the kings of Leon (today, the crown prince of Spain still bears the formal title of Prince of Asturias). In this rugged, far-off part of Spain, Romanization had been less intense, and it had also most successfully resisted Visigoth hegemony. As stated diplomatically by David Pharies: “The inhabitants of this region probably learn a somewhat simplified Latin … The Romance vernacular that arises from this Latin then evolves without the benefit of a strong learned tradition.” This is echoed by Penny: “…Spanish has its geographical roots in … an area remote from the centres of economic activity and cultural prestige in Roman Spain, which was latinized fairly late, and where the Latin spoken must consequently have been particularly remote from the prestige norm (that is, particularly ‘incorrect’)…”

In the tenth century, for the first time, there is reference to the region of the upper Ebro Valley as “Castilla”, the land of the many castles, referring to the numerous fortresses that had been constructed in those parts to safeguard Leon against Muslim attacks. Castile became an independent county in 981CE, and was recognized as a separate Christian kingdom in 1004CE. Castile truly came to the fore through its conquest in 1085CE of Toledo, the old Visigoth capital of Spain, followed by its part (together with Aragon and Navarre) in the pivotal battle of Navas de Tolosa in 1212CE, which effectively broke Muslim military might in Iberia.

As the Moors were driven south, Vulgar Latin once again became the dominant language of Iberia, especially its variant the Castilian dialect. In 1230 Castile absorbed Leon and in 1236 its forces took Córdoba, the erstwhile capital of the Moslem Caliphate – another prestige-enhancing feat. By the middle of the 13th century, after the region of Murcia was re-conquered by the then king of Castile and León, King Alfonso X (who was called “El Sabio” – the wise or learned king), the Castilian language had gained pre-eminence among the Vulgar Latin dialects in Iberia. With large parts of Spain now under his rule, Alfonso X began moving the country toward adopting a standardized language based on the Castilian dialect. He and his court of scholars adopted the city of Toledo, the old cultural center in the central highlands, as the base of their activities. There, scholars wrote original works in Castilian and translated histories, chronicles, and scientific, legal, and literary works from other languages (principally Latin, Greek, and Arabic). Indeed, this historic effort of translation was a major vehicle for the dissemination of knowledge throughout ancient Western Europe. Alfonso X decreed that Castilian be used in his realm for all official documents and other administrative work.

As the Moors were driven south, Vulgar Latin once again became the dominant language of Iberia, especially its variant the Castilian dialect. In 1230 Castile absorbed Leon and in 1236 its forces took Córdoba, the erstwhile capital of the Moslem Caliphate – another prestige-enhancing feat. By the middle of the 13th century, after the region of Murcia was re-conquered by the then king of Castile and León, King Alfonso X (who was called “El Sabio” – the wise or learned king), the Castilian language had gained pre-eminence among the Vulgar Latin dialects in Iberia. With large parts of Spain now under his rule, Alfonso X began moving the country toward adopting a standardized language based on the Castilian dialect. He and his court of scholars adopted the city of Toledo, the old cultural center in the central highlands, as the base of their activities. There, scholars wrote original works in Castilian and translated histories, chronicles, and scientific, legal, and literary works from other languages (principally Latin, Greek, and Arabic). Indeed, this historic effort of translation was a major vehicle for the dissemination of knowledge throughout ancient Western Europe. Alfonso X decreed that Castilian be used in his realm for all official documents and other administrative work.

In 1469 another important event in Spanish history took place. Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile married, and united the two main kingdoms of the Peninsula under one monarchy. They also decreed Castilian to be the official language of the realm. This set in motion the creation of the Kingdom of Spain, and the beginning of the modern era in the region.

Columbus brings Castilian to the Americas – 1492

In 1492 Columbus took the flag of Castile to the Americas, and thus was born the far-flung Spanish empire. It should be noted, however, that Castilian was most influential in shaping the Spanish spoken in the Americas near its seats of administrative power. In these regional capitals (located mostly in highland areas, such as Mexico City, Antigua Guatemala, Bogota) the dominant influence was from court officials, clergy and academics sent there – they were educated, from Madrid and the north of Spain, and were steeped in Castilian.

When looking more broadly at the type of Spanish spoken in the Americas, it is evident that the dialect typically spoken in Spain’s south-western port city of Seville (then Spain’s largest and wealthiest city, with a monopoly on trade with the Americas) and in the Canary Islands (closely related to the western Andalusian Spanish of the region around Seville, and influential as way-station towards the Americas) significantly shaped the Spanish of the lowlands and the parts of America further removed from the seats of the Castilian-speaking bureaucracy.

Most of the common settlers and soldiers, and especially the women who colonized the Americas were from the poor, less educated regions of the south-west (Andalusia and the Canary Islands) and their speech quite naturally influenced the areas where they settled, which were often remote from the seats of learning comfortably ensconced on the cooler highlands. This has given rise to the distinct modern-day speech divergence between Spanish as spoken in the American lowlands and in the highlands – with the lowland variant being more informal, rapid-fire and for example tending not to pronounce the “s”. A common heritage from Canarian / western Andalusian Spanish across all of the Americas, is the fact that ustedes is used without contrast between second-person-plural formal and informal – in clear distinction to the Castilian norm of differentiating.

Another typical speech characteristic distinguishing the Spanish of the Americas from that of Iberia, is the use in the Americas of the “idiomatic” (compounded) future tense construct of ir + verb infinitive, instead of the simple future tense and its conjugations.

The Codification of Spanish Grammar

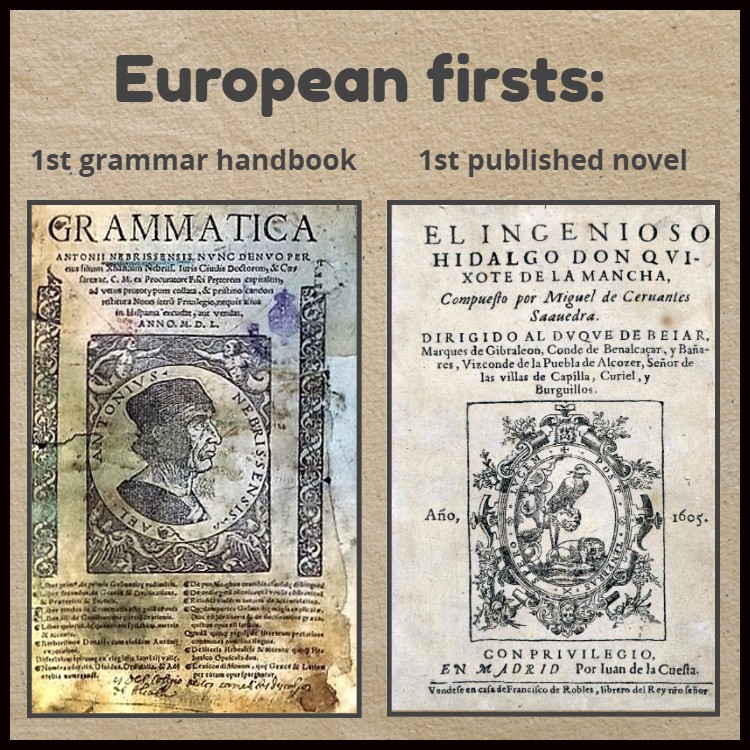

The Gramática de la Lengua Castellana, by Elio Antonio de Nebrija (written in Salamanca in 1492 – the year of the fall of Granada and the discovery of the Americas by Columbus), has the distinction of having been the first grammar handbook ever written for a modern European language. (Similarly, Don Quijote by Miguel de Cervantes was the first ever novel written in a modern European language). According to a popular anecdote, when Nebrija presented his handbook to Queen Isabella I, she asked him what was the use of such a work. He answered that language is the instrument of empire – as he also wrote in his introduction to the grammar, dated August 18, 1492 “… language was always the companion of empire.”

Very importantly, Nebrija’s first dictum in his handbook was that Spaniards should write (i.e., spell & apply grammar) as they speak, and speak as they write. Thanks in no small measure to this early stance, Spanish is today fortunate to have easy-to-learn spelling that largely follows the pronunciation of words.

The Real Academia Española (English: Royal Spanish Academy), generally abbreviated as RAE, was founded in 1713. It is the official royal institution responsible for overseeing the Spanish language. The RAE is based in Madrid, Spain, but is affiliated with national language academies in twenty-one other hispanophone nations through the Association of Spanish Language Academies. The RAE’s motto is “Limpia, fija y da esplendor” (“[it] cleans, sets, and gives splendor”). The RAE dedicates itself to promoting linguistic unity within and between the various Hispanic territories of the world, to ensure a common standard in accordance with Article 1 of its founding charter: “… to ensure the changes that the Spanish language undergoes … do not break the essential unity it enjoys throughout the Spanish-speaking world.”

Quite naturally there are variations in the spoken Spanish of the various regions of Spain, as well as variations throughout the Spanish-speaking areas of the Americas. In Spain, northern dialects are popularly thought of as being closer to the desired standard, although positive attitudes toward southern dialects have increased significantly in the last 50 years. Even so, the speech of Madrid is the standard variety for use on radio and television, and is the variety that has most influenced the written standard for Spanish. There is, however, no notion that any variation originating from, for example, the Americas, is “wrong”. (Consequently, the DELE / SIEL / OPIc exam tests comprehension of all kinds of Spanish accents, and there is NO SINGLE PREFERRED or more “CORRECT” FORM OF SPANISH FOR EXPRESSING YOURSELF IN THES TESTS – i.e., you do not have to try and speak / sound like a Madrileño!).

I hope that you have seen now the reasoning behind why Spanish history is part of the DELE exam curriculum. For a better idea of how the rest of the DELE exam curriculum is composed, ask for our FREE in-house Workbook #9 “DELE / SIELE Exam Orientation and Acing Tips“. It is an e-book of some 96 pages, which I would be happy to send you free, as a sample of our study material. Just send me your e-mail address with our convenient contact information form by clicking on the image below (this entails no obligation to register for coaching with us).

Good luck with your exam preparation!

Salu2

Willem